If strolling along litter-strewn European beaches you ever console yourself with the thought of the far north – the last stronghold of wilderness, where beaches do not as yet look like rubbish dumps – you’re in for a bit of a disappointment. The Arctic is drowning in litter.

Collated by Barbara Jóźwiak, forScience Foundation

The situation looks grim even in protected areas, such as Sørkapp, where direct human impact is virtually non-existent.

Sørkapp (or, to be more specific, Sørkappland) is the southernmost tip of Spitsbergen. It may well be that once Hornbreen and Hambergbreen glaciers have receded, it will become a separate island. For the time being, however, it’s part of Sør-Spitsbergen National Park. It consists mainly of mountains, glaciers and Arctic tundra, with Palffyodden – along with our headquarters (code name: Awfully Rotten Cabin) – located at its north-western edge.

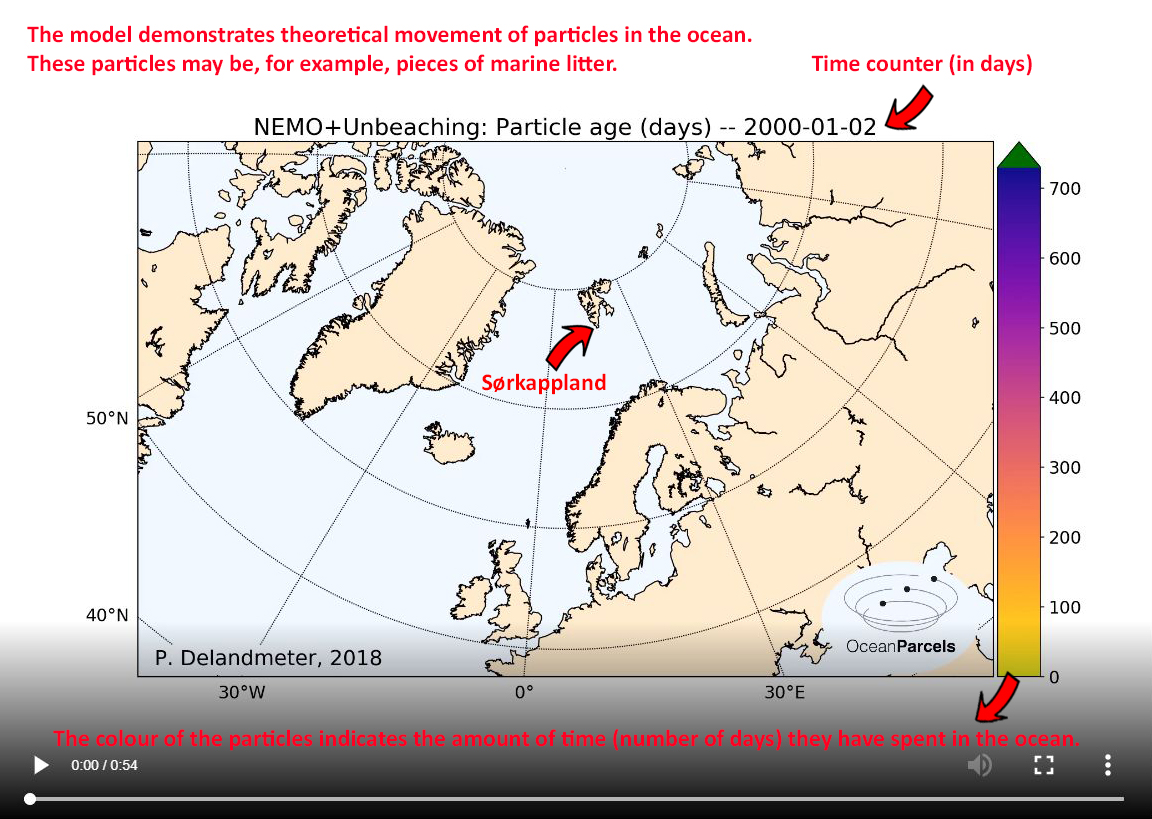

Apart from a few species of animals, the area is uninhabited. Guests arrive rarely because there’s no tourist infrastructure or public transport, and non-public alternatives are not only outrageously expensive but also entirely dependent on the weather, which tends to be far from perfect. To complicate the logistics even further, no scientific research, camping or trekking can be done in the area without an official permit from the Governor of Svalbard. Still, despite the broadly understood inaccessibility, unwanted signs of human presence are visible at every turn – wherever you look, the coast is strewn with litter. Where does it come from? Europe1Granted, the Polish Polar Station Hornsund is just across the fiord, but we pass it over in our litter-related considerations as we’re convinced that the scientists who stay there are serious enough to dispose of their rubbish according to the rules., for one. Carried by winds and ocean currents, marine litter reaches the “dead end” of the Arctic in less than two years. And more often than not, this is where it stays.

If you’d like to learn more about the topic, here you can read about how our litter ends up in the ocean (even if we don’t throw it in there) and here – trace its journey from Europe to the most remote corners of the Arctic2If you find the animation confusing, scroll all the way down for a brief explanation of what it shows..

Restricted access, which makes it unlikely for Sørkapp to become littered in the traditional sense of the word, leaves it defenceless against the litter coming from the outside, because there is no one around to pick up what the waves are bringing in. As a result, marine litter accumulates along the coastline, where it’s not just a blot on the landscape but also a serious threat to local fauna.

Despite annual beach clean-ups carried out as part of the Clean up Svalbard campaign in numerous locations throughout the archipelago, no such action has ever been recorded in our target area. In other words, we’ll be the first to tackle marine litter washed ashore in this region.

Why has this stretch of the coast been skipped so far? There are at least a few reasons. Apart from logistic problems we have already mentioned, it’s also necessary to take into account potential hazards in the form of numerous skerries (sharp underwater rocks) and breaking waves near the shore. Less dangerous but equally troublesome is frequent fog or, for example, slippery masses of rotting seaweed. Moreover, cruise ships taking part in Clean up Svalbard do not normally venture into these parts, as most of them head north, which is where the star attraction of Svalbard – the polar bear – is much easier to spot.

On the right: Polar bears © Nikita Ovsyanikov, Irina Menyushina

Yet another complication has to do with the fact that the area is scattered with archaeological sites and objects recognized as cultural heritage. Clean up enthusiasts must therefore be extra careful not to remove any items which despite looking like litter are anything but.

As you can see, there are quite a few difficulties ahead of us, but because marine litter makes nothing of them so will we. Before we follow the litter to the Arctic, however, we’ll still manage to tell you about the preparations we’re making, awesome people we’ve met in the process, and about the fact that – despite all the Arctic-bound currents – working on the project is not always plain sailing.